Cyber Security Web Applications

Web Applications are integral to almost everything we do, whether it is to access the Internet or to remotely control your lawnmower. In this introduction class we will cover the basics of web application security.

The HTTP protocol

HTTP is the carrier protocol which allows our browsers and applications to receive content such as HTML ("Hyper Text Markup Language"), CSS ("Cascading Style Sheets"), images and videos.

URLs, Query Parameters and Scheme

To access a web application we use a URL ("Uniform Resource Locator"), for example: https://www.google.com/search?q=w3schools+cyber+security&ie=UTF-8

The URL to google.com contains a domain, a script being accessed and Query Parameters.

The script we are accessing is called /search. The / indicates it is contained in the top directory on the server where files are being served. The ? indicates the input parameters to the script and the & delimits different input parameters. In our URL the input parameters are:

- q with a value of w3schools cyber security

- ie with a value of UTF-8

The meaning of these inputs is up to the webservers application to determine.

Sometimes you will see just / or /? indicating that a script has been setup to serve to respond to this address. Typically this script is something like an index file which catches all requests unless a specific script is specified.

The Scheme is what defined the protocol to use. In our case it is the first part of the URL: https. When the scheme is not defined in the URL it allows the application to decide what to use. Schemes can include an entire array of protocols such as:

- HTTP

- HTTPS

- FTP

- SSH

- SMB

HTTP Headers

The HTTP protocol uses many headers, some custom to the application and others well defined and accepted by the technology.

Example request to http://google.com

GET /search?q=w3schools+cyber+security&ie=UTF-8 HTTP/1.1

Host: google.com

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/87.0.4280.88 Safari/537.36

Accept: image/avif,image/webp,image/apng,image/*,*/*;q=0.8

Referer: https://w3schools.com/

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Cookie: cookie1=value1;cookie2=value2

The request header specifies what the client wants to perform on the target webserver. It also has information regarding if it accepts compression, what kind of client is accessing and any cookies the server has told the client to present. The HTTP request headers are explained here:

| Header | Explanation |

|---|---|

| GET /search... HTTP/1.1 | GET is the verb we are using to access the application. Explained in detail in the section HTTP Verbs. We also see the path and query parameters and HTTP version |

| Host: google.com | This header indicates the target service we want to use. A server can have multiple services as explained in the section on VHOSTS. |

| User-Agent | A client application, that is the browser in most cases, can identify itself with the version, engine and operating system |

| Accept | Defines which content the client can accept |

| Referer: https://w3schools.com/ | If the client clicked a link from a different website the Referer header is used to say from where the client came from |

| Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate | Can the content be compressed or encoded? This defines what we can accept |

| Cookie | Cookies are values sent by the server in previous requests which the client sends back in every subsequent request. Explained in detail in the section State |

With this request, the server will reply with headers and content. Example headers are seen below:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html

Set-Cookie: <cookie value>

<website content>

The response header and content is what determines what we will see in our browser. The HTTP response headers are explained as following:

| Header | Explanation |

|---|---|

| HTTP/1.1 200 OK | The HTTP Response code. Explained in detail in the HTTP Response Codes section |

| Content-Type: text/html | Specifies the type of content being returned, e.g. HTML, JSON or XML |

| Set-Cookie: | Any special values the client should remember and return in the next request |

HTTP Verbs

When accessing a web application the client is instructed on how to send data to the web application. There are many verbs which can be accepted by the application.

| !Verb | Used for |

|---|---|

| GET | Typically used to retrieve values via Query Parameters |

| POST | Used to send data to a script via values in the body of the Request sent to the webserver. Typically it involves creating, uploading or sending large quantities of data |

| PUT | Often use to upload or write data to the webserver |

| DELETE | Indicate a resource which should be deleted |

| PATCH | Can be used to update a resource with a new value |

These are used as the web application requires. Restful (REST) web services are especially good at using the full array of HTTP Verbs to define what should be done on the backend.

HTTP Response Codes

The application running on the webserver can respond with different codes based on what occurred on the server side. Listed are common response codes the webserver will issue to the client which security professionals should know about:

| Code | Explanation |

|---|---|

| 200 | Application returned normally |

| 301 | Server asks client to permanently remember a redirect to a new location where the client should access |

| 302 | Redirect temporarily. Client doesn't need to save this reply |

| 400 | The client made an invalid request |

| 403 | The client is not allowed to access this resource. Authorization is required |

| 404 | The client tried to access a resource which does not exist |

| 500 | The server errored in trying to fulfill the request |

REST

Rest services, sometimes called RESTful services, employ the full force of HTTP Verbs and HTTP Response Codes to facilitate the use of the web application. RESTful services often uses parts of the URL as a query parameter to determine what happens on the web application. REST is typically used by API's ("Application Programming Interfaces").

REST URLs will invoke functionality based on the different elements of the URL.

An example REST URL: http://example.com/users/search/w3schools

This URL will invoke functionality as part of the URL instead of Query Parameters. We can decipher the URL as:

| Parameter | Comment |

|---|---|

| users | Accessing the users part of the functionality |

| search | Accessing the search feature |

| w3schools | The user to search for |

Sessions & State

There is no built in way for a server to identify a returning visitor in HTTP. For a webserver to identify the user, a secret value must be communicated to and from the Client in each request. This is typically done via Cookies in headers, however other ways are also common such as via GET and POST parameters or other headers. Passing state via GET parameters is not recommended as such parameters are often logged on the server or in intermediaries such as a proxy.

Here are some common Cookie examples which allows the application on the webserver to control sessions and state:

- PHPSESSID

- JSESSIONID

- ASP.NET_SessionID

These values represent a certain state, often called a session, on the server. This state represents things like:

- What user you have logged in as

- Privileges and authorizations

It is important that session value, sent to the Client, can not be easily guessed or otherwise identified by others. If they could, an attacker could then present themselves as other users on the web application.

State can also be saved on the client. This involves the server sending all the states to the client and relies on the client sending back all the items. Such implementations relies on encryption to check the integrity of the state the client is claiming. Examples of implementations using this is listed below:

- JWT ("JSON Web Tokens")

- ASP.Net ViewState

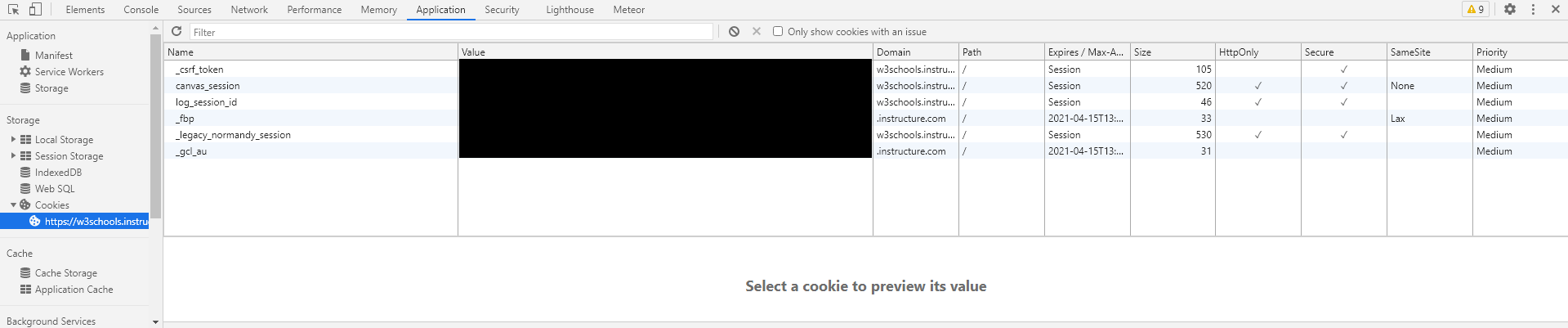

You are using cookies to take this class! You can inspect these cookies in your web browser by opening up the developer tools. This is done by hitting F12 within the browser, opening up the developer tools window. Within this window you should be able to find the correct place where your cookies are stored.

In Google Chrome, the cookies were identified in the Application tab above.

Virtual Hosts

One webserver can process many applications via Virtual Hosts, often abbreviated as Vhosts. To facilitate access to other Virtual Hosts the web server typically reads off the Host header of the client request, and based on this value sends the request to the correct application.

URL Encoding

For an application to safely transfer content between the server and client, some characters must be encoded to ensure they do not impact the protocol. To preserve the integrity of the communications, URL encoding is used.

URL Encoding replaces unsafe characters with a % and two hexadecimal digits. For example:

- Percentage is replaced with %25

- Space is replaced with %20

- Quote is replaced with %22

An excellent tool to perform text analysis and run operations such as URL Decoding is CyberChef. You can try it out in your browser here: https://gchq.github.io/CyberChef/

JavaScript

To support dynamic content, browsers use the scripting language JavaScript. This enables developers to program solutions which will run on the client, enabling more interactive and "alive" web-content.

JavaScript is also involved in many attacks against web-applications and client applications such as browsers.

Encryption with TLS

The HTTP protocol does not support encryption for data-in-transit, hence a wrapper around HTTP is added for encryption support. This is indicated with a S following HTTP, i.e. HTTPS.

The encryption used to be SSL ("Secure Sockets Layer"), but has since been deprecated. Instead TLS ("Transport Layer Security") is typically used to enforce encryption.